Hearing voices allowed Charles Dickens to create extraordinary fictional worlds

The novelist said he did not invent, but merely recorded what he heard and saw. This prompts questions about the act of writing

• Hearing voices: What's your experience when reading?

• Hearing voices: What's your experience when reading?

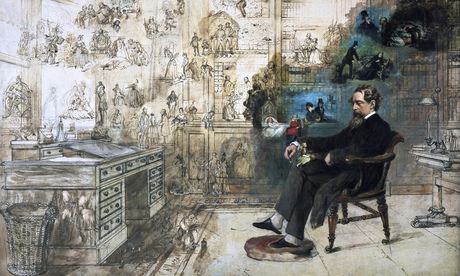

Dickens' Dream … Charles Dickens in his Gad’s Hill Place study, in Higham, Kent, conjuring up his characters while asleep. Detail from the watercolour sketch by Robert William Buss. Courtesy of The Charles Dickens Museum

Evelyn Waugh's A Handful of Dust (1934) ends with its protagonist, Tony Last, trapped in the Brazilian jungle by his captor, Mr Todd, who compels him to read aloud the complete works of Charles Dickens, in sequence, over and over, without end – or escape. It's a fantastically dark conceit: the great Victorian novelist as the sadist's accomplice. It also links Dickens to the possibility that there is something potentially oppressive, even imprisoning, in experiencing the human voice. Voices, it suggests, may tyrannise the mind.

Waugh linked Dickens elsewhere with hearing voices. In The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold (1957), most notably, the middle-aged writer Pinfold suffers an acute mental crisis while at sea, repeatedly hearing the thrum of human voices coming from the ship's pipes. Or so he assumes: in fact, these voices are persistent, imaginary, and unsolicited – that is, auditory verbal hallucinations, seemingly related to Pinfold's dependency on alcohol and sedatives (Waugh wrote from first-hand experience). The voices follow Pinfold around wherever he wanders on the ship, causing increasing perturbation. And the ship's captain has the unmistakably Dickensian name Steerforth (after James Steerforth in David Copperfield, another sadistic master).

Most modern readers may feel instinctively that literary experience has much in common with the act of overhearing. Reading fiction is a process of allowing characters' voices to sound in the inner ear, and absorbing the imagined noise they make (magically cued by curls of ink on a page). It's common to think of writers, too, building fictional worlds through voices, as if creativity begins as a subtle internal overhearing. The analogy between imagining and hearing certainly runs deep in our myths of culture. Inspiration, that theory of composition at once ancient, Romantic, and modern, tells us that creativity ignites by admitting some mysterious other voice into the writer's flow of being. To write means having one's voice disrupted, taken over, rendered by another. Dickens believed this, too.

Later in his career, Dickens's vocal impersonations of his own characters gave this truth a theatrical form: the public reading tour. Although wisdom has it that "doing" the different voices of his cherished characters hastened his death, no other Victorian could match him for celebrity, earnings, and sheer vocal artistry. The Victorians craved the author's multiple voices: between 1853 and his death in 1870, Dickens performed about 470 times. "Amid all the variety of 'readings', those of Mr Charles Dickens stand alone," beamed the Times in 1868. Edgar Johnson, his first post-Freudian biographer, wrote in the 1950s: "It was [always] more than a reading; it was an extraordinary exhibition of acting that seized upon its auditors with a mesmeric possession."

Hearing voices and inventing character were also indivisible aspects of his creativity. Dickens understood his astonishing writing practice as the summoning of voices. "Every word said by his characters was distinctly heard by him," one critic stressed in 1872. Dickens himself considered his novels to come from some autonomous source beyond volition, as he wrote to his friend John Forster: "when I sit down to my book, some beneficent power shows it all to me, and tempts me to be interested, and I don't invent it – really do not – but see it, and write it down". How literally he meant this is hard to judge. But allowing in unsolicited presences was central to his self-understanding as a writer. Mrs Gamp, the disreputable nurse from Martin Chuzzlewit, intruded repeatedly on Dickens when he was writing that novel, "whispering to him in the most inopportune places – sometimes even in church – that he was compelled to fight her off by force", as the American writer JM Peebles later put it.

Like mesmerism, which he took up, illusion and hallucination were topics of serious interest to Dickens. An essay of 1857, My Ghosts, published in his own journal Household Words, explored these fragile mental states. And his fiction features unanchored voices, such as in his 1866 Christmas story The Signal-Man, which begins with the sudden intrusion of an unidentified voice bellowing "Halloa!" out of nowhere. Members of theinternational hearing voices movement today argue that voices represent a part of the person that wants to be heard and acknowledged. Whether modern theories help us to better understand Dickens, or vice versa, seems unclear. But he was an exemplary source of voices, as both a writer and performer, in ways that should ask us to consider how we culturally frame literary creativity, inner speech and audition, and unusual mental experience.

* Peter Garratt is a lecturer in the department of English studies at Durham University and a participating researcher on the Hearing the Voice project.